Less Screen, More Story: Why Libraries Matter More Than Ever

Last week, we were delighted to welcome Helen Hayes MP to the Upper Norwood Library Hub, where I have the privilege of serving as a Trustee. Helen is our local…

February 4th 2026

There are some books that arrive at exactly the right moment, and Babies’ and Toddlers’ Rights in Practice by Mary Moloney, Dr Sharon Skehill and Dr. Jennifer Pope is one of them. At a time when early childhood education is often pulled towards outcomes, measurement, and speed, this book gently but firmly re-centres our attention on babies and toddlers as rights-bearing citizens, not future pupils-in-waiting.

What I particularly value is the way the authors translate the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child into the lived, everyday reality of practice from birth to three. Drawing on national and international curricula, including the updated Aistear framework link, they challenge adult-centred assumptions about what very young children can understand and contribute. The reminder from UNICEF (2021) that children as young as two can identify rights such as clean water, food, play, and being heard feels both powerful and sobering. These are not abstract ideas; they are exactly what babies and toddlers should experience daily in high-quality early years settings.

This book takes a refreshing angle. Rather than focusing primarily on developmental milestones or educational needs, it highlights rights, agency and relational pedagogy, and crucially, it makes these concepts tangible. The NOD approach (Noticing, Observing and Documenting) and the STRIVE framework are practical, thoughtful tools that help teachers and educators embed rights-respecting practice into routines that already exist, rather than adding yet another layer of expectation.

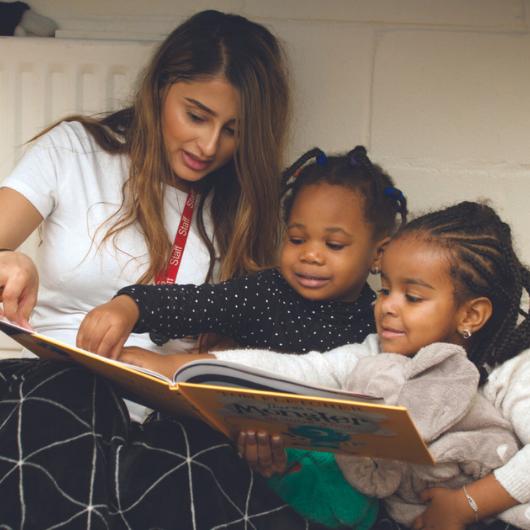

I found the structure particularly accessible. Each chapter stands alone, with clear headings, practice scenarios, and reflective prompts, making it an ideal book for students, apprentices, and busy teachers and educators who may dip in and out as needed. The emphasis on relational pedagogy runs throughout, reminding us that pedagogy is not something separate from care, but is expressed in feeding, changing nappies, settling children to sleep, singing, talking, and simply being present. I especially appreciated the chapter on pedagogy, which explains this concept with clarity and humility, stripping away jargon and rooting it firmly in relationships.

The authors’ attention to attachment theory, including clear references to Bowlby and the key person approach, is both reassuring and necessary. Too many new entrants to the sector have limited exposure to these foundations, despite their central importance for babies’ emotional security and learning. The focus on language and “serve and return” interactions is equally welcome, recognising that communication begins long before words, through gaze, gesture, babbling and shared attention.

I was also drawn to the discussion of slow pedagogy and unhurried routines, echoing contemporary thinking about deep attention and deep listening. Slow here is not about time dragging, but about intentionality, calm, and presence, creating conditions in which babies and toddlers can truly flourish. Routines are rightly framed not as interruptions to learning, but as rich pedagogical and caring spaces in their own right.

The image of the child that emerges from this book is strong, consistent and hopeful: active, competent, heard, and respected. The engagement with Malaguzzi’s Hundred Languages and Lundy’s participation model adds depth, and I was pleased to see babies and toddlers positioned as local and global citizens, a chapter that resonated deeply with my own work on sustainability, compassion and citizenship. The language of courage, care and compassion weaves quietly but confidently through the text.

The section on pedagogical leadership and advocacy is a timely reminder that leadership in early years is about safeguarding the quality of children’s everyday lives while staying intellectually curious and open to new ideas. This is not passive work; it is ethical, political, and purposeful.

This is a book I will return to often. It is thoughtful without being heavy, principled without being prescriptive, and practical without losing its moral compass. It will certainly be one I recommend to our apprentices and colleagues, and one that deserves a place on the shelf of anyone committed to seeing babies and toddlers not just as cared for, but as respected, rights-holding members of our communities.

Last week, we were delighted to welcome Helen Hayes MP to the Upper Norwood Library Hub, where I have the privilege of serving as a Trustee. Helen is our local…

Launching the Reading Rights Summit in Liverpool Last week, Booktrust (where I proudly serve as a Trustee) hosted the Reading Rights Summit. We were joined by special guests, the…

It is Good to Talk! The signs of things going wrong in society are usually first evident in small children. The widespread dependence on Smartphones is…